This JanTerm, Professor David Moody transported his FlagSHIP students through international landscapes and cultural histories—all from campus. His secret? Tabletop games.

“I'm using games to simulate another world and asking students to play, inherently simulating travel study abroad,” Professor Moody said. “Every game has an element of simulation. When you play that game, you’re living something else. And that’s the goal of FlagSHIP, to get students to live something else.”

Professor Moody & his self-curated "game cart"

More than half of the 2025 JanTerm FlagSHIP courses were held locally, uncovering new insights in the College’s backyard. Among these, Moody's "Creativity, Culture, and Kobolds" course stood out. Students explored classic tabletop games like Monopoly, Catan, and Dungeons & Dragons, examining how these games create immersive environments, tell stories, and reflect the cultures that produced them.

“Whether a student’s traveling to Italy to learn about the Italian lifestyle or staying on Flagler’s campus and playing board games, they should come away with some sense of a different way of living,” Moody said. “They're using the games as a lens to look at the way other people live.”

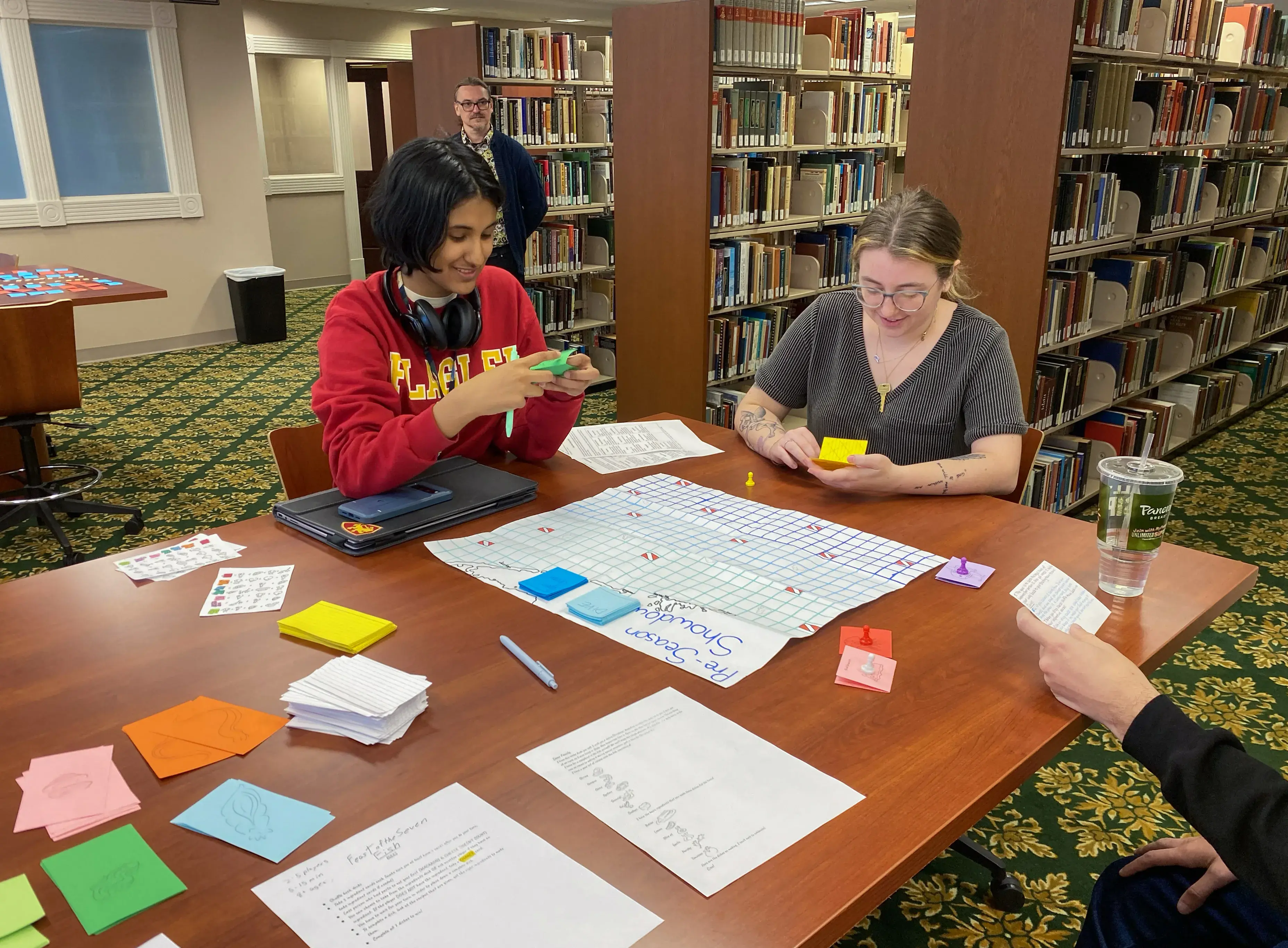

By playing and analyzing, then designing their own tabletop games, students in Moody’s FlagSHIP gained a more authentic understanding of global perspectives they may have otherwise left unexplored.

“They go to whatever the game represents as an alternative to [their lived experience], so they can come back with new knowledge from that simulated experience,” he explained.

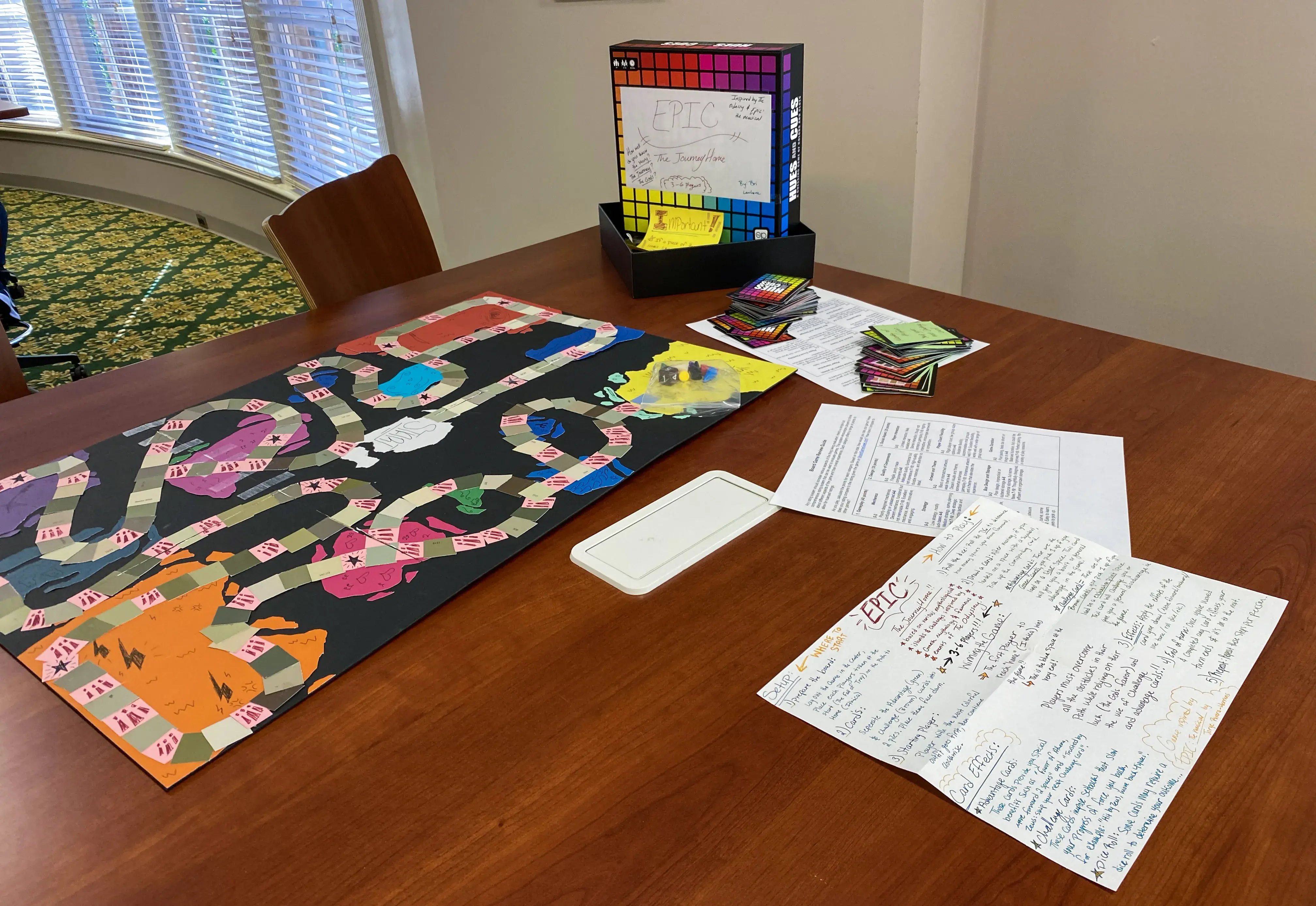

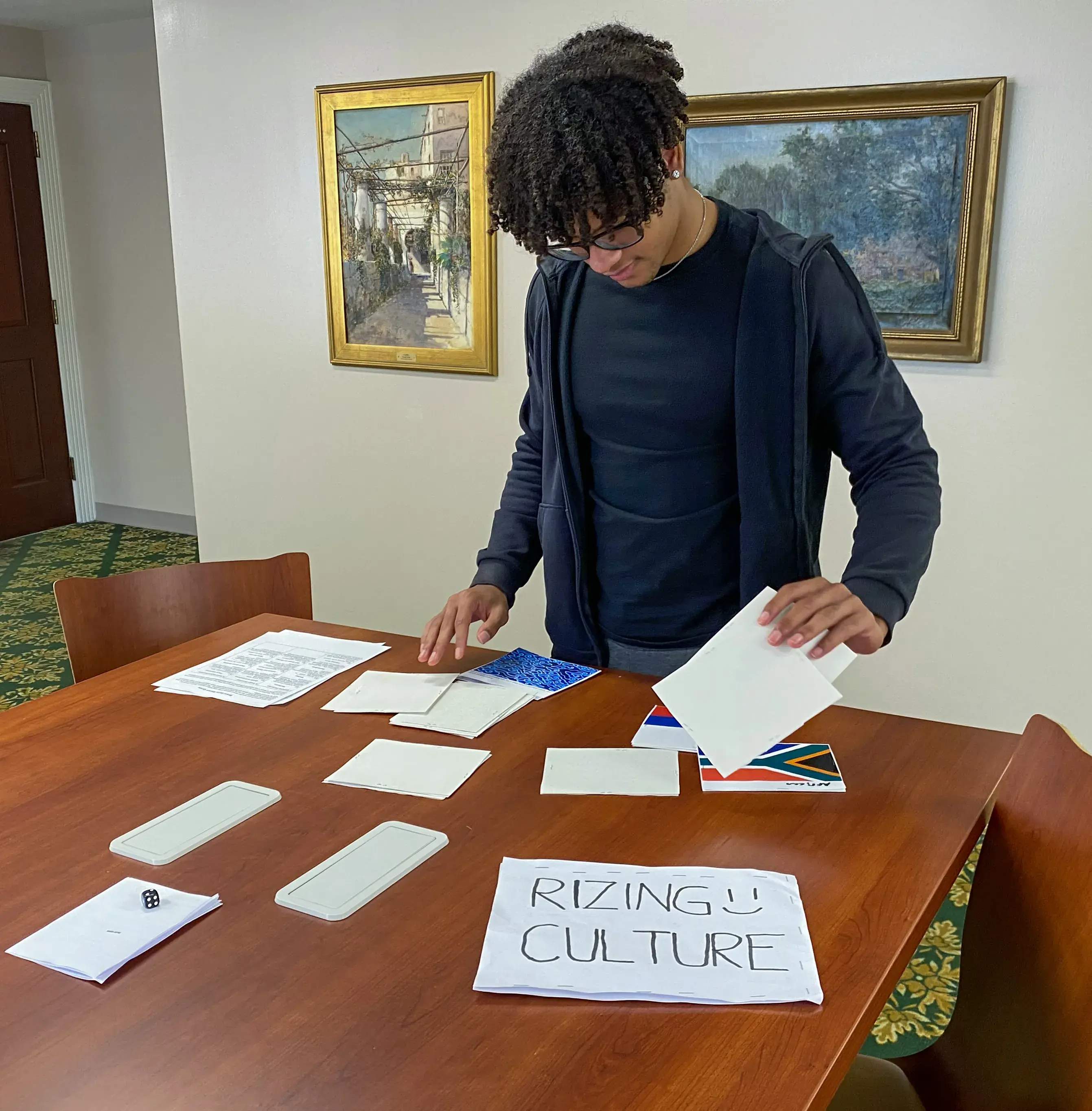

For the final project, students create a board game representing a culture or community they want to share or explore.

“As they design their own tabletop experiences, they tap into the same instincts that have driven storytelling and strategy for centuries,” Moody said. “We play games to test ideas, to imagine different ways of living, and to connect with each other.”

Moody encourages students to deeply research and identify cultural elements from outside their own experiences. They then "gamify" these aspects, creating games that let others feel what it's like to experience life in another country or culture. This process also helps students acquire skills in game design, narratology (the study of storytelling), and ludology (the study of game mechanics).

Student-made game "EPIC"

In the same vein of game design skill acquisition, Moody assigns an exercise for the students to re-skin a Monopoly board to reflect Flagler College, encouraging them to think critically about various aspects of the college and its surroundings. This in-class project helps students think critically about their community and culture by using the familiar structure of the Monopoly game.

He guided their creativity with open-ended questions like "What does free parking become at Flagler College?" and "What does going to jail look like at Flagler College?"

This activity bleeds into a broader class discussion on game design and its potential to reflect and critique societal structures. Moody emphasizes the value of Monopoly as a tool to represent community, culture, and struggle.

"Monopoly was an invaluable resource to us,” he said.

Zooming out, this FlagSHIP underscores that games have long been integral to humanity, serving purposes like conflict simulation, community building, and spiritual exploration.

“Every culture has games,” he said. “Whether they're board games, card games, or dice games might depend on the technology available to support the game system."

Some of the earliest known tabletop games include “Senet” from ancient Egypt (around 3100 BCE) and “Go” from China (around 2000 BCE). Moody said these games, played by nobility, held cultural and religious significance.

"The further back we look in history- art, books, games, plays- it's all going to have a religious tie-in because that was how the world was structured. Ancient Egyptians, for example, used Senet to figure out where their place in the afterlife would be,” he said. “Contemporary games lose that.”

Moody shed light on the broader social, technological, and cultural shifts that often influence the evolution and creation of games. He cited significant historical moments like the Enlightenment, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the Great Depression that influenced tabletop game design or evolution in distinct ways.

“Using board games as a lens for the past is more useful than using them as a lens for the future,” Moody said.

He explained that Monopoly originated from Elizabeth Magie's 1904 game, The Landlord’s Game. This original version was designed to illustrate the adverse effects of land monopolies and rent on tenants. The game had two rule sets: one for wealth accumulation and one for anti-monopolistic principles.

Over time, Moody said players preferred the “fantasy” of the wealth accumulation aspect, leading to the modern Monopoly game we know today.

“Monopoly became popular right after the Great Depression,” Moody said. “Naturally, people wanted to live in a pretend space of wealth.”

Moody’s FlagSHIP addresses the powerful psychological phenomena of escapism and imagination in gameplay that can transform any table into a theatrical stage where players can freely make-believe.

“You can be an absolute jerk in Monopoly to your friends, and everyone laughs about it because, 'the game made me do it,’ or ‘the game gave us permission to do it’,” he said. “In the act of play, we all buy into the notion that we are doing something collectively, together safely, and whatever happens within this space is allowed.”

As Moody defines it, “play” is something done in a safe space that allows flexibility for testing and developing new ideas.

“Without play, how can a politician come up with a new law, or a teacher come up with a new class?" He asked.

He pushes the students to challenge the common belief that play is only for children or that games are merely a pastime from a more leisurely era.

"We play games to remember our capacities for survival and creativity, and I think we often lose that as we age,” Moody said. “The further we go into adulthood and seriousness, we start looking at play as optional or as something ‘only a kid would do,’ and we lose what it is to be innocent, creative, and exploratory.”

Moody acknowledges that the value of play can be challenged or even “lost altogether” as people mature. But regardless of how common losing our childhood sense of play may be, he assures students that it doesn’t have to be that way.

“Students don’t just study games in the course; they experience firsthand how play shapes culture, builds connections, and prompts new ways of thinking,” he said, with a forward-thinking optimism. “Play is a creative, critical tool that, if permitted, we can carry with us into adulthood. If it gets lost along the way, classes like this one can help us reclaim it. That’s why it is so important as part of FlagSHIP and the Flagler experience.”