Michigan 2025 Fieldwork

Overview

Overview

Over the course of thirteen days (May 9 - May 23, 2025), Dr. Yiorgo Topalidis had the honor and privilege of visiting with and learning from descendants of Ottoman Greek migrants in Michigan. While there, he traveled 625 miles, conducted 32 interviews, and documented 2892 images. This information will be added to the Ottoman Greeks of the US Digital History archive.

The following short essays present highlights from those interviews.

Fieldwork, Day-by-Day

Fieldwork, Day-by-Day

Day 1 – Bullying, and Agency in National Allegiance

Day 1 – Bullying, and Agency in National Allegiance

On the first day of research in Michigan, we learned about the complexities of national allegiance and racial identity from descendants of Ottoman Greek immigrants. One respondent, “Maria,” recalled her grandfather’s enlistment and service in the Ottoman Army from 1917 to 1919.

He was discharged and then proceeded to enlist and serve in the Greek Army from 1920 until the final retreat in 1922. He purchased this wallet in Bursa while he was enlisted in the Greek Army and kept a prayer pamphlet in it titled, "The Apocalypse of the Virgin Mary," which “kept him safe from everything” during his time on the front line. A second respondent, “Georgia,” lived through the Detroit race riots or the Detroit uprising and experienced physical violence in school.

Day 2 - The Bible in Karamanlidika

Day 2 - The Bible in Karamanlidika

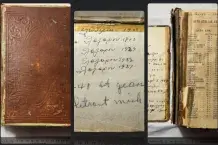

Day two of research in Michigan, and we were honored to receive this precious artifact. This bible dates back to 1900 and was donated to the OGUS archive by Mrs. Shirley Collias and her daughter Peggy.

It was brought to the U.S. from Semendire, located in the Anatolian region of the Ottoman Empire, and consists of Karamanlidika script. Karamanlidika is the designation for the Ottoman language written using the Greek alphabet.

Day 3 - The Death March from Aydin

Day 3 - The Death March from Aydin

On the third day of our research trip in Michigan, we learned about a family’s connection to the massacre of Aydın, one of many massacres against Ottoman Greeks that collectively indicate an organized effort by the Ottoman government to commit ethnic cleansing and genocide.

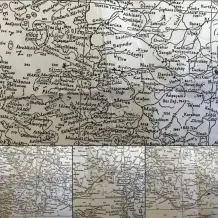

Ms. Becky Patouhas contributed the map shown at left, on which her grandfather marked the locations that he, her great-grandmother, and her grand aunt were marched from Koçarir (Aydın) to Adana, both located in the Anatolian region of the Ottoman Empire.

Only her grandfather survived the journey.

Day 4 - Release from the Labor Battalions

Day 4 - Release from the Labor Battalions

On the first day of our research trip in Michigan, we learned about an Ottoman Greek migrant who enlisted in and served the Ottoman Army for two years before being discharged. He subsequently enlisted in the Greek Army.

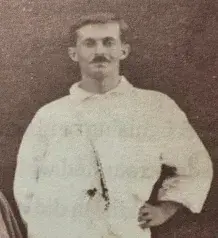

On day four, we encountered the story of Yianni Hatzigabrielides, who was taken from his family in 1919 and transferred to the infamous Labor Battalions.

He was forced to work to near death and survived only because, at war’s end in 1922, he was released. He and the remnants of Ottoman Greeks from the labor battalion began a journey eastward on foot.

He eventually reached Beirut and, with the help of a local Greek shopkeeper, connected with the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, which assisted him in finding and reunifying with his family. This is a photograph of Yiannis, a year after his arrival in Florina.

Day 5 - The Choha

Day 5 - The Choha

This image depicts a “Choha.” According to Ms. Elizabeth Bizbikis, this was the wedding dress worn by her grandmother in Semendire, Turkey (ca. 1905). According to Ms. Bizbikis, the striped dress is called the “Enteri” and was worn beneath the choha. Both were covered by the silver embroidered apron which was one of two in existence in Semendire, while a shawl covered the bride’s head.

The family and the choha moved to Istanbul prior to the exchange of populations and established themselves there. In a subsequent trip, a family friend transferred the choha to Elizabeth’s mother in Pontiac, Mich. This photo depicts Ms. Bizbikis’s mother wearing the choha.

Day 6 - Semendre Brotherhood and Benevolent Society

Day 6 - Semendre Brotherhood and Benevolent Society

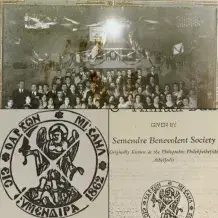

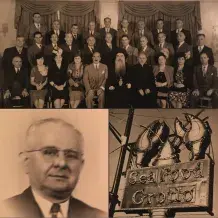

Like Alsatians in Fort Worth, Texas, and Somerville, Mass., Marmarians in Los Angeles, Spokane, and Seattle, Washington, and Pontians in Canton, Ohio, Philadelphia, Jersey City, N.J. and New York City, the Semendrians moved en masse, first to Spokane, Wash., and then to Detroit and Pontiac, Mich.

On Day 6, we learned that, upon arrival, they organized a mutual aid society named the Semendre Brotherhood and Benevolent Society. According to the Brotherhood’s records, the first chapter was established in 1913, in Tacoma, Wash. The Society was first known as the Philanthropic and Philomathic Brotherhood, “Taxiarches."

Members of the Brotherhood organized picnics and dances and fundraised to build St. George Greek Orthodox Church in Pontiac.

Day 7 - Greek Orthodox Easter in Korea

Day 7 - Greek Orthodox Easter in Korea

On the seventh day of our research trip to Michigan, we interviewed Mr. John Iakovides. Mr. Iakovides is a second-generation descendant of immigrants from Fertek and Delmos. He enlisted in the US Army and served in Korea. Both of his parents spoke Turkish at home, which he learned in conversation from them.

While in Korea in 1952, his multilingualism proved to be a valuable asset. He gravitated towards a Greek regiment, which employed him to mediate the transfer of materials from a Turkish regiment in order for the former to prepare a collection of lambs for Greek Orthodox Easter. This photo is of the Greek regiment roasting the lambs with Mr. Iakovides in the foreground.

Day 8 - Life in Cadillac, Mich.

Day 8 - Life in Cadillac, Mich.

Like many other immigrants who arrived in the U.S. between 1900-1924, yesterday we were reminded that settlement did not always occur in an ethnic immigrant enclave.

Such was the case of Mr. George (Kakoglou) Nicholas. He first immigrated in 1914 and settled in Cadillac, Mich. According to his son, also named George, his father owned one of a handful of Greek-owned cafes in the small town, which served American cuisine. Cadillac does not, and has not, had a Greek Orthodox church. When his aunt, Belighia (Pelagia?) Kakoglou, was married in January of 1922 in the adjacent, equally small town of Big Rapids, Mich., St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church was used for the nuptials.

This photo depicts her wedding day.

Day 9 – Silence

Day 9 – Silence

On the eve of the commemoration of the Pontic Greek genocide (annually on May 19), and our ninth day of research in Michigan, we interviewed Mr. Michael and Vasiliki Kosmides.

This photograph is of Michael’s parents, both born near Trapezounta (Trk. Trabzon). Mr. Kosmides never met either of his maternal or paternal grandparents. His parents never discussed his grandparents’ lives in the Ottoman Empire, save for some small bits and pieces of information. He does not know how his parents arrived in Greece, nor how they settled in Polyplatanos, Florina. “They never talked about it,” he said.

This silence is a recurring theme in our interviews and is well-documented and interpreted by migration scholarship. Migrants and in particular, displaced persons, asylum seekers, and refugees typically do not share their traumatic experiences with the second generation (ie, their children). More frequently, this information is passed on to the third generation

Day 10 - Assimilation and Upward Mobility

Day 10 - Assimilation and Upward Mobility

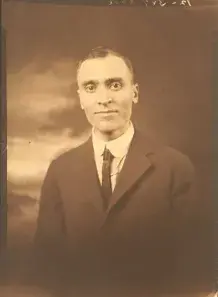

On the tenth day of our research trip in Michigan, Mrs. Athena Papageorgiou provided us with a lesson about segmented assimilation and upward mobility. Her maternal grandfather migrated from Asia Minor to Detroit before the destruction of Smyrna (Trk. Izmir) and established himself as a successful restaurateur.

James Konstantinidis owned the Seafood Grotto in Detroit for his entire life, and what a life it was. Athena described her grandfather as a generous and gregarious figure. He served and led the council of St. Constantine and Helen’s for multiple terms, was a decorated member of the Knights of St. Andrew, and regularly hosted clergy at his home and restaurant. He also participated in and funded the activities of American, Greek, and Ottoman Greek organizations such as the American Legion, the Messenian Society, and the Federation of Micrasiatic Societies of the United States and Canada.

Day 11 - Escape from the Ottoman Army

Day 11 - Escape from the Ottoman Army

Day eleven of our research trip in Michigan provided us with another candid view of the Semendrian community’s migration to Pontiac. Sofia Papatheodore and Moshoula Yaksich, sisters, discussed their father’s migration.

He was a musician and was drafted into the Ottoman Army, where he served as an entertainer for a short period before being reassigned to the front during World War I. He refused, and the Ottoman officers informed him that he would be punished if he did not go.

Sofia said: “He went AWOL. He said, ‘I won’t fight against my brothers.'” Traveling by night, he walked back to Semendire. With the end of the war, he and some of his friends left Semendire. He traveled first to Constantinople (Trk. Istanbul) and then landed at Ellis Island. He worked as a dishwasher in New York, and at his uncle's request, who was in Pontiac, he moved there and became the owner of Star Grocery.

Day 12 - The Blanket

Day 12 - The Blanket

For day twelve of our research trip in Michigan, Ms. Angelynn Afendoulis took us on a journey back to Ordu, located in the Anatolian region of the Ottoman Empire, and sharedher ten-year-old aunt’s experience of a march to Constantinople. In 1917, she was separated from her family at the port of Ordu. While her family escaped to Kyiv, she returned to Angelynn’s grandmother’s house for safety, only to find herself forced to march to Constantinople with her aunt and four cousins four years later.

“She talked about … marching in the pouring rain. She said she was 10 years old and little, and she had a 30-pound backpack [on her back] and [was] soaking wet. She talked about how my grandmother was beaten with a whip for whatever set of reasons by one of the soldiers. My grandmother buried her three youngest children… a little girl and two boys. The girl was killed by a soldier who threw a rock at her head, and the boys died of starvation.

My dad used to talk about a blanket that my grandmother had in the basement of their house in Grand Rapids, that she held her daughter in as the child died. She would take that out of the rafters and just hold it and rock and cry. [Also] she believed …all her life that she buried one of her sons alive.”

This photo is of Angelynn’s grandmother in Ordu before her expulsion.

Day 13 - "Aren't they human beings?"

Day 13 - "Aren't they human beings?"

On the final day of our research trip in Michigan, we were reminded about the fragile position of Ottoman Greek migrant identity within the boundary of American White supremacist Whiteness. In our last interview, the respondents shared the following recollection regarding their maternal grandfather’s tenure as a restaurateur in Depression-era Kentucky.

Respondent A: “The Ku Klux Klan ran him out of town.”

Respondent B: “He had a restaurant, and he was serving Black people, and (the KKK) were very upset with him. And he said, ‘(The Black people) weren't being served by the other people!’ What do they care who I served?’ Is how he had put it. ‘Aren't they human beings?’”

Respondent A: “They burned it down, and ran him out, and he left and came [to Detroit] scared.”

As indicated by his grandchildren, his unwillingness to conform to the dehumanization of Blacks placed him outside the boundary of White supremacist Whiteness and made him the target of racial violence. In response, he spent the rest of his life teaching his children and grandchildren the virtues of empathy, equality, and justice.